1 Bayes’ Theorem

1.1 Introduction

Bayes’ theorem is at the core of modern uncertainty quantification.

Theorem 1.1 (Bayes Theorem) If we have two events, \(a\) and \(b,\) then \[ P(b \vert a) = \frac{P(a\vert b) P(b)}{P(a)}, \] where \(P(a \vert b)\) is the conditional probability of \(a\) given \(b.\)

In a more general setting, suppose that we have observations, \(y_{\mathrm{obs}} \in \mathbb{R}^{N_y},\) of a state variable, \(x,\) then the conditional PDF, \(\pi_X(x \vert y_{\mathrm{obs}}),\) is given by Bayes’ formula \[ \pi_X(x \vert y_{\mathrm{obs}}) = \frac{ \pi_Y( y_{\mathrm{obs}} \vert x) \pi_X(x)} {\pi_Y(y_{\mathrm{obs}}) }. \]

Here,

- \(\pi_X,\) the prior PDF, quantifies our uncertainty about the state/parameters \(X\) before observing \(y_{\mathrm{obs}},\) while

- \(\pi_X(x \vert y_{\mathrm{obs}}),\) the posterior PDF, quantifies our uncertainty after observing \(y_{\mathrm{obs}}.\)

- The conditional PDF \(\pi_Y( y_{\mathrm{obs}} \vert x)\) quantifies the likelihood of observing \(y\) given a particular value of \(x.\)

- Finally, the denominator, \(\pi_Y(y_{\mathrm{obs}}),\) is simply a normalizing factor, and can be computed in a post-processing step.

We thus rewrite the formula in Theorem 1.1 as

\[ \pi_X(x \vert y_{\mathrm{obs}}) \propto \pi_Y( y_{\mathrm{obs}} \vert x) \pi_X(x), \]

or,

\[ p(\mathrm{parameter}\mid\mathrm{data})\propto p(\mathrm{data}\mid\mathrm{parameter})\, p(\mathrm{parameter}), \]

if we are dealing with a parameter-identification inverse problem.

1.2 Bayesian Regression

1.2.1 Classical Linear Regression

We recall the classical linear regression models. We present a general formulation that will prepare the terrain for the Bayesian approach.

Recall that in a regression problem we want to model the relationship between a dependent variable, \(y,\) that is observed and independent variables, \({x_1,x_2, \ldots, x_p},\) that represent the properties of a process (James et al. 2021). We have at our disposal \(n\) data samples \[\begin{equation}\label{eq:linreg_data} {\cal D}=\{ (\mathbf {x}_i,\,y_i),\; i=1,\dots, n \} , \end{equation}\] from which we can estimate the relationship between \(y\) and \(x,\) where \(\mathbf {x}_i = [x_{i1}, x_{i2}, \ldots, x_{ip}] \in \mathbb{R}^p .\)

The data pairs come from observations, and we postulate a linear relationship between them of the form \[\begin{align*} y_{i} & =\mathbf{x}_{i} \boldsymbol{\beta}+\epsilon_{i}, \quad i=1,\ldots,n,\\ & =\beta_{0}+\beta_{1}x_{i1}+\beta_{2}x_{i2}+\cdots+\beta_{p}x_{ip}+\epsilon_{i}, \end{align*}\] where

- \(x_{ij}\) is the \(i\)-th value of the \(j\)-th covariate, \(j=1,\ldots,p,\)

- \(\boldsymbol{\beta}=[\beta_0,\beta_1,\ldots,\beta_p]^\mathrm{T},\)

- and \(\epsilon_i\) are independent, identically distributed normal random variables, with mean zero and variance \(\sigma^2,\) \[ \epsilon_{i}\sim\mathcal{N}(0,\sigma^{2}). \]

We rewrite this in matrix-vector notation as \[\begin{equation} \mathbf{y} = X \boldsymbol{\beta}+\boldsymbol{\epsilon}, \end{equation}\] where the augmented matrix \[ X=\left[\begin{array}{ccccc} 1 & x_{11} & x_{12} & \cdots & x_{1p}\\ 1 & x_{21} & x_{22} & \cdots & x_{2p}\\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots\\ 1 & x_{1p} & x_{2p} & \cdots & x_{np} \end{array}\right] \tag{1.1}\] and \[ \mathbf{y} = \left[\begin{array}{c} y_1 \\ \vdots \\ y_n \end{array}\right]. \] An alternative way of writing this system, that will be needed below, is obtained by noticing that \[ y_{i} - \mathbf{x}_{i} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \epsilon_{i}, \] which implies that the probability distribution of \[ y_{i} - \mathbf{x}_{i} \boldsymbol{\beta} \sim \mathcal{N}(0,\sigma^{2}) \] and hence that the probability distribution of each observation is Gaussian, \[ y_{i} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{x}_{i} \boldsymbol{\beta},\sigma^{2}), \] or, in vector form, \[ \mathbf{y} \sim \mathcal{N}(X \boldsymbol{\beta},\sigma^{2}I), \] where \(I\) is the identity matrix.

For simplicity, let us consider the special case of a straight line regression for a single covariate, \(x,\) \[ y_i = \beta_{0}+\beta_{1}x_{i},\quad i=1,\ldots,n. \] Then classical least squares regression consists of finding \((\beta_{0},\beta_{1})\) that minimizes the sum of the squared errors \[ E=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\epsilon_{i}^{2}, \] where \[ \epsilon_{i} = \left|\beta_0+ \beta_1 x_{i}-y_{i}\right|. \] The minimum was found by solving the equations for the optimum, \[ \frac{\partial E}{\partial\beta_0}=0\,,\quad\frac{\partial E}{\partial\beta_1}=0. \] We find the two equations \[\begin{eqnarray*} \left(\sum_{i=1}^{n}1\right)\beta_0+\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n}x_{i}\right)\beta_1 & = & \sum_{i=1}^{n}y_{i},\\ \left(\sum_{i=1}^{n}x_{i}\right)\beta_0+\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n}x_{i}^{2}\right)\beta_1 & = & \sum_{i=1}^{n}x_{i}y_{i}. \end{eqnarray*}\] This can be rewritten as the following matrix system, \[ X^{\mathrm{T}} X \boldsymbol{\beta} = X^{\mathrm{T}} \mathbf{y} , \tag{1.2}\] with \[ X=\left[\begin{array}{cc} 1 & x_{1} \\ 1 & x_{2} \\ \vdots & \vdots \\ 1 & x_{n} \end{array}\right], \quad \mathbf{y} =\left[\begin{array}{c} y_{1}\\ \vdots\\ y_{n} \end{array}\right] \quad\mathrm{and}\quad \boldsymbol{\beta} =\left[\begin{array}{c} \beta_0\\ \beta_1 \end{array}\right]. \]

In this univariate case, the system (Equation 1.2) can be solved explicitly. We obtain the optimal, least-squares parameter estimations, \[ \beta_0 = \bar{y}-\bar{x} \beta_1 , \quad \beta_1 = \sigma_{xy}/\sigma_{x}^{2}, \] where the empirical means and variances are given by \[ \bar{y}=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}y_{i},\quad\bar{x}=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}x_{i} \] and \[ \sigma^2_{xy}=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(x_{i}-\bar{x}\right)\left(y_{i}-\bar{y}\right),\quad\sigma_{x}^{2}=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(x_{i}-\bar{x}\right)^{2}. \]

Recall the general result expressed now in terms of linear regression.

Theorem 1.2 (Linear Regression) For \(X \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times p},\) \(\boldsymbol{\beta} \in \mathbb{R}^{p},\) and \(\mathbf{y} \in\mathbb{R}^{n},\) let \(\epsilon=\epsilon(x)= X \boldsymbol{\beta} - \mathbf{y}.\) The general least-squares problem for linear regression is to find the vector \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) that minimizes the residual sum of squares, \[

\sum_{i=1}^{n}\epsilon_{i}^{2}=\epsilon^{\mathrm{T}}\epsilon=( X \boldsymbol{\beta} - \mathbf{y})^{\mathrm{T}}( X \boldsymbol{\beta} - \mathbf{y}).

\] Any vector that provides a minimal value is called a least-squares solution. The set of all least-squares solutions is precisely the set of solutions of the normal equations, \[

X^{\mathrm{T}}X \boldsymbol{\beta} = X^{\mathrm{T}}\mathbf{y}.

\]

There exists a unique least-squares solution, given by \(\boldsymbol{\beta} =\left(X^{\mathrm{T}}X\right)^{-1}X^{\mathrm{T}}\mathbf{y},\) if and only if \(\mathrm{rank}(X)=p.\)

1.2.2 Bayesian Linear Regression

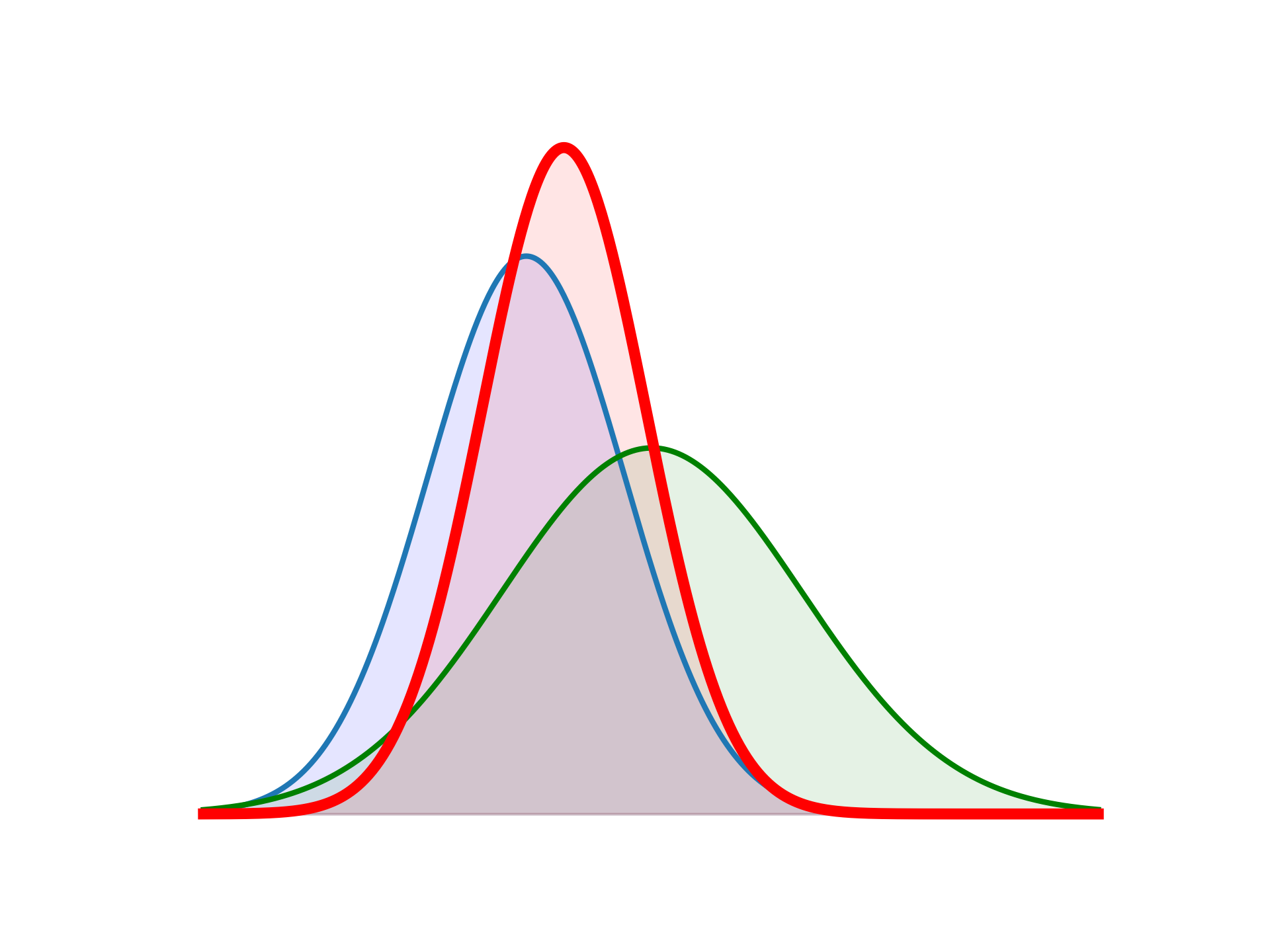

We can now generalize to the case of Bayesian regression. In the Bayesian approach, not only the error term is random, but the elements of the model parameter vector \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) are also considered to be random variables. We also suppose that we have a prior distribution \(p(\boldsymbol{\beta})\) available before any data are observed. Then, as observation data \(X\) become available, the initial probabilities of the parameters can be updated to a posterior probability distribution, according to Bayes’ Law. This posterior is a refined, narrower distribution and provides not only a better estimate of the parameters, but also a complete uncertainty quantification.

Recall our linear model (Equation 1.1), \[ \mathbf{y} = X \boldsymbol{\beta} + \boldsymbol{\epsilon}, \] where the noise term is assumed to be Gaussian. The probabilistic model for regression is then a conditional probability, \[ p(\mathbf{y} \mid X, \boldsymbol{\beta} ) = \mathcal{N} \left(\mathbf{y} \mid \mu_X , \Sigma_X \right) \] and the Bayesian regression problem is to estimate the posterior probability distribution of the parameters, \(p(\boldsymbol{\theta} \mid \mathbf{y}),\) where \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) includes \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) and can also include the constant noise variance \(\sigma^2,\) where \(\Sigma_X = \sigma^2 I\) and \(I\) is the identity matrix. In the above case, \(\mu_X = X \boldsymbol{\beta}\) is a linear function of \(X,\) but, in general, linear regression can be extended to non-linear cases by simply replacing \(X\) by a non-linear function of the inputs, \(\phi(X).\) This is called basis function expansion, and in particular, when \(\phi(X)=[1,x,x^2,\ldots,x^d],\) we obtain polynomial regression.

In general, we need to perform the following steps:

- Specify the prior distribution of the parameters, \(\boldsymbol{\beta}.\) Note that the prior law can either be known (from historical data or models, for example), or its parameters can be included in the estimation process.

- Specify the distribution of the noise term. This is always taken as Gaussian in the case of regression analysis. As before, its parameter (variance) is either known, or can be inferred.

- Compute the likelihood function of the parameters, using the noise distribution and the independence of each observation.

- Calculate the posterior distribution of the parameters from the prior and the likelihood.

1.3 Some Examples

1.3.1 Bayesian Linear Regression—Univariate, Scalar Parameter Case

As seen above, the simplest linear regression problem for a univariate independent variable, \(x,\) is defined as \[ y_i = \beta_{0}+\beta_{1}x_{i} + \epsilon_{i},\quad i=1,\ldots,n, \] where \[ \epsilon_{i}\sim\mathcal{N}(0,\sigma^{2}) \] and we assume that the individual observations are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.). As a first step, we consider the case of estimating a noisy scalar, with \(\beta_0 = \beta,\) \(\beta_1 =0\) and \[ y_i = \beta + \epsilon_{i},\quad i=1,\ldots,n. \] We are in possession of a Gaussian prior distribution for \(\beta,\) \[ \beta \sim\mathcal{N}(\mu_{\beta },\sigma_{\beta }^{2}) \] with expectation \(\mu_{\beta }\) and variance \(\sigma^2_{\beta },\) which could come from historical data or some other model, for example. We also have \(n\) independent, noisy observations, \[ \mathbf{y}=\left(y_{1},y_{2},\ldots,y_{n}\right). \]

The conditional distribution of the observations, given the data, is thus the distribution of the noise term, shifted by the data value (since the expectation of \(\beta\) is equal to \(\beta\) and the expectation of the noise is zero), \[ y_{i}\mid \beta \sim\mathcal{N}(\beta,\sigma^{2}) \] where we have conditioned on the true value of the parameter \(\beta.\) Then, thanks to the i.i.d. property, the conditional distribution of the observations, or likelihood, is a product of Gaussians, \[\begin{eqnarray} \label{eq:Gauss_likeli_scalar} p(\mathbf{y}\mid \beta) & = & \prod_{i=1}^{n}\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^{2}}}\exp\left\{ -\frac{1}{2\sigma^{2}}\left(y_{i}-\beta\right)^{2}\right\} \\ & \propto & \exp\left\{ -\frac{1}{2\sigma^{2}}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(y_{i}-\beta\right)^{2}\right\} \nonumber. \end{eqnarray}\] Now, according to Bayes’ Law (\(\ref{eq:Bayes-2}\)), the posterior (inverse) distribution of the data given the measurements is \[ p(\beta \mid\mathbf{y})\propto p(\mathbf{y}\mid \beta)p(\beta), \] so, using the data likelihood and the prior distributions, we have \[\begin{eqnarray*} p(\beta \mid \mathbf{y}) & \propto & \exp\left\{ -\frac{1}{2}\sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{ \left(y_{i}-\beta\right)^{2}}{\sigma^{2}} + \frac{\left(\beta-\mu_{\beta}\right)^{2}}{\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}\right\} \\ & \propto & \exp\left\{ -\frac{1}{2}\left[\beta^{2}\left(\frac{n}{\sigma^{2}}+\frac{1}{\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}\right)-2\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n}\frac{y_{i}}{\sigma^{2}}+\frac{\mu_{\beta}}{\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}\right)\beta\right]\right\} . \end{eqnarray*}\] Notice that this is the product of two Gaussians which, by completing the square, can be show to be Gaussian itself. We obtain the posterior Gaussian distribution, \[\begin{equation} \label{eq:post_gaussian_scalar1} \beta \mid \mathbf{y}\sim\mathcal{N}\left(\mu_{\beta\mid\mathbf{y}},\sigma_{\beta\mid\mathbf{y}}^{2}\right), \end{equation}\] where \[\begin{equation}\label{eq:post_gaussian_scalar1_mu} \mu_{\beta\mid\mathbf{y}}=\left(\frac{n}{\sigma^{2}}+\frac{1}{\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}\right)^{-1}\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n}\frac{y_{i}}{\sigma^{2}}+\frac{\mu_{\beta}}{\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}\right) \end{equation}\] and \[\begin{equation}\label{eq:post_gaussian_scalar1_sig} \sigma_{\beta\mid\mathbf{y}}^{2}=\left(\frac{n}{\sigma^{2}}+\frac{1}{\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}\right)^{-1}. \end{equation}\] Let us now examine more closely these two parameters of the posterior law. There are two important observations here:

- The inverse of the posterior variance, called the posterior , is equal to the sum of the prior precision, \(1/\sigma_{\beta}^{2},\) and the data precision, \(n/\sigma^{2}.\)

- The posterior mean, or conditional expectation, can also be written as a sum of two terms, \[\begin{eqnarray*} \mathrm{E}(\beta\mid\mathbf{y}) & = & \frac{\sigma^{2}\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}{\sigma^{2}+n\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}\left(\frac{n}{\sigma^{2}}\bar {y}+\frac{\mu_{\beta}}{\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}\right)\\ & = & w_{y}\bar{y}+w_{\mu_{\beta}}\mu_{\beta}, \end{eqnarray*}\] where the sample mean, \[ \bar{y}=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}y_{i} \] and the two weights, \[ w_{y}=\frac{n\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}{\sigma^{2}+n\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}\,,\quad w_{\mu_{\beta}}=\frac{\sigma^{2}}{\sigma^{2}+n\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}, \] add up to \[ w_{y}+w_{\mu_{\beta}}=1. \]

We observe immediately that the posterior mean is the weighted sum, or weighted average, of the data mean, \(\bar{y},\) and the prior mean, \(\mu_{\beta}.\) Now let us examine the weights themselves.

- If there is a large uncertaintyin the prior, then \(\sigma_{\beta}^{2}\rightarrow\infty\) and hence \(w_{y}\rightarrow1,\) \(w_{\mu_{\beta}}\rightarrow 0\) and the likelihood dominates the prior,leading to what is known as the sampling distribution for the posterior, \[ p(\beta\mid\mathbf{y})\rightarrow\mathcal{N}(\bar{y},\sigma^{2}/n). \]

- If we have a large number of observations, then \(n\rightarrow\infty,\) implying that \(w_{\mu_{\beta}}\rightarrow 0,\) and the posterior now tends to the sample mean, whereas if we have few observations, then \(n \rightarrow 0\) and the posterior \[ p(\beta\mid\mathbf{y})\rightarrow\mathcal{N}(\mu_{\beta},\sigma_{\beta}^{2}) \] tends to the prior.

- In the case of equal uncertainties between data and prior, \(\sigma^{2}=\sigma_{\beta}^{2}\) and the prior mean has the weight of a single additional observation.

- Finally, if the uncertainties are small, either the prior is infinitely more precise than the data (\(\sigma_{\beta}^{2}\rightarrow0\)) or the data are perfectly precise (\(\sigma^{2}\rightarrow0\)).

We end this example by rewriting the posterior mean and variance in a special form. Let us start with the mean \[ \begin{eqnarray} \mathrm{E}(\beta\mid\mathbf{y}) & = & \mu_{\beta}+\frac{n\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}{\sigma^{2}+n\sigma_{\beta}^{2}}\left(\bar{y}-\mu_{\beta}\right),\nonumber \\ & = & \mu_{\beta}+G\left(\bar{y}-\mu_{\beta}\right). \end{eqnarray} \tag{1.3}\] We conclude that the prior mean \(\mu_{\beta}\) is adjusted towards the sample mean \(\bar{y}\) by a gain (or amplification factor) of \(G=1/(1+\sigma^{2}/n\sigma_{\beta}^{2}),\) multiplied by the innovation \(\bar{y}-\mu_{\beta},\) and we observe that the variance ratio, between data and prior, plays the essential role. In the same way, the posterior variance can be reformulated as \[ \sigma_{\beta\mid\mathbf{y}}^{2}=(1-G)\sigma_{\beta}^{2} \tag{1.4}\] and the posterior variance is thus updated from the prior variance according to the same gain \(G.\)

These last two equations, (Equation 1.3) and (Equation 1.4), are fundamental for a good understanding of Bayesian parameter estimation (BPE) and of Data Assimilation, since they clearly express the interplay between prior and data, and the effect that each has on the posterior.

1.3.2 Other Examples

Many more examples can be found in (Asch 2022).