SUMO

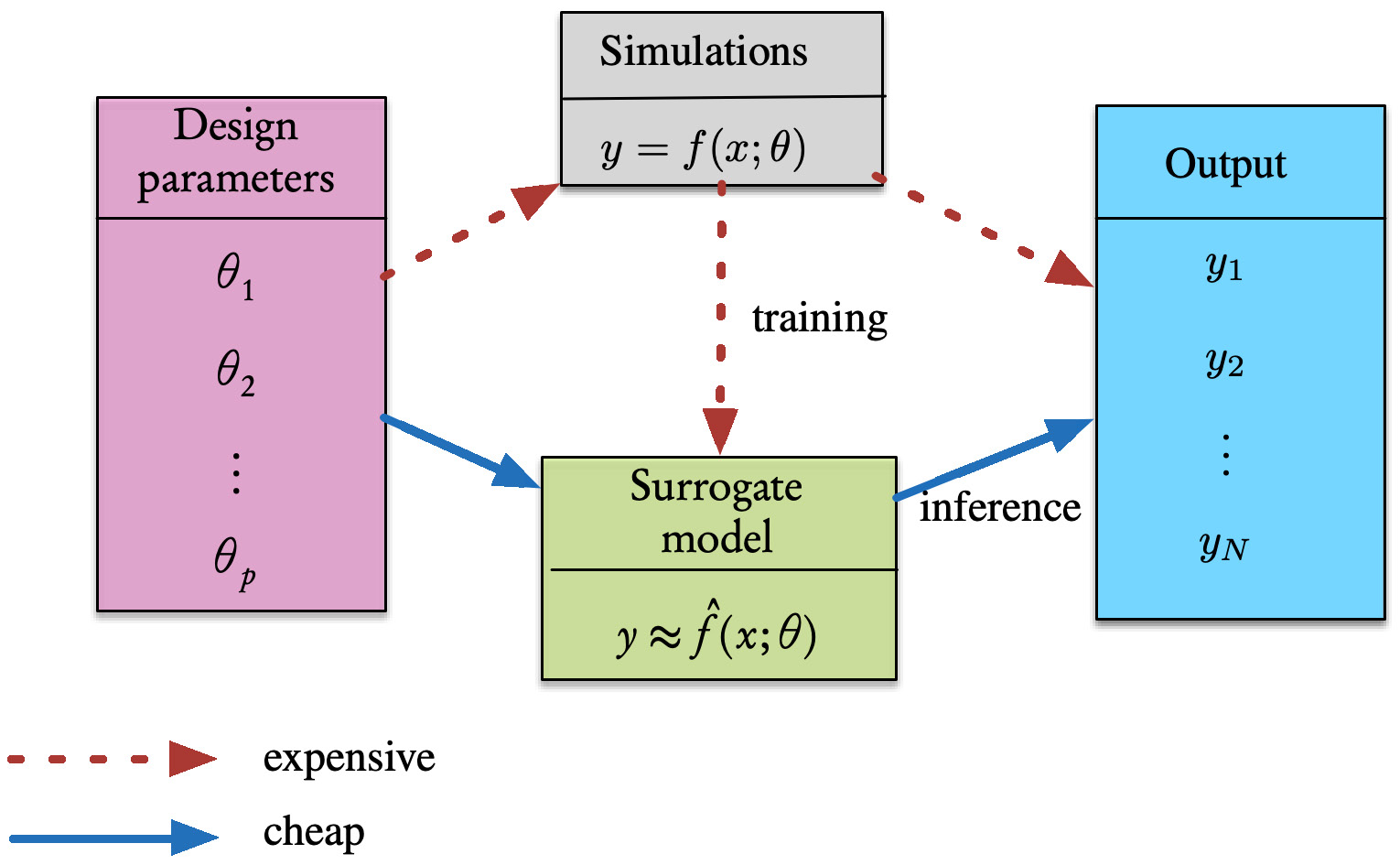

In a recent paper, we have explored the use of surrogate models (SUMO) for the optimal design of an important phase in Li-ion battery manufacturing. Our data come from simulations that have been shown to faithfully reproduce real experimental conditions. However:

- The design space is very large.

- The simulations are very compute-intensive and have long CPU times.

- For some parameter combinations, the simulations have convergence difficulties.

The challenge here is to replace the computational model by a suitable surrogate model that will:

- Capture the complex underlying physico-chemistry.

- Once trained, enable very rapid inferencing for optimal choice of the manufacturing parameters.

In summary: we seek a digital twin of the process. Here is a schematic description of the general principles of the Surrogate Modeling process.

The expensive steps are performed (once) offline, and then the trained model can be used in quasi-real time, or in some outer-loop optimization, as described in the book.

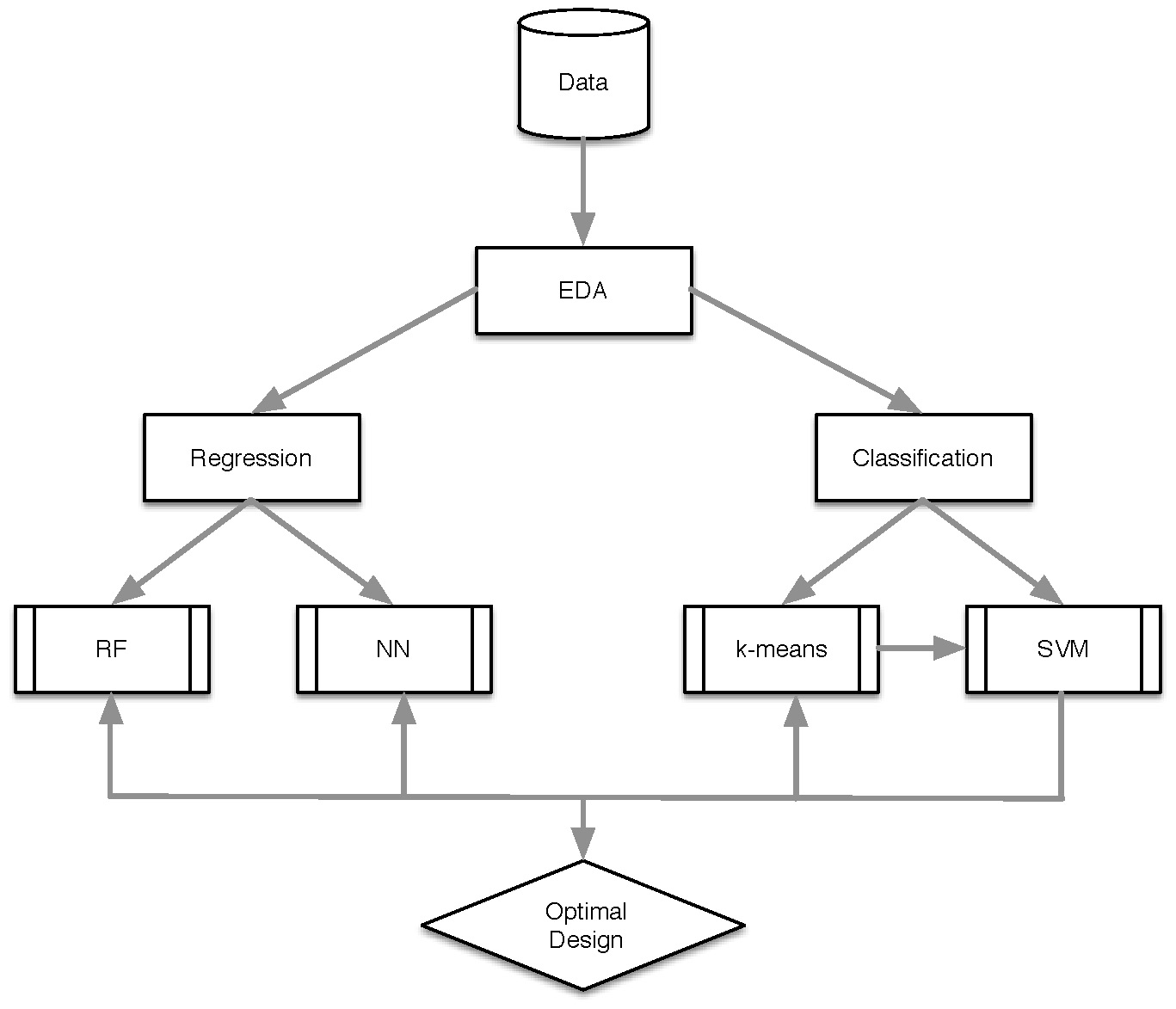

In the actual case considered, electrolyte wetting and filling of an electrode, we employed a sequence of simple, unsupervised and supervised learning techniques, preceeded by an exploratory data analysis step. This is depicted in the following flowchart.

We insist on the fact that the approach is generic, in that it can be applied to any (your) data, as is. Of course, the “devil is in the details” and you will have to tune each method at each step, depending on the nature and properties of the data. However, the guiding principles can be stated as follows:

- EDA is mandatory, and its importance should not be underestimated. It is indispensable for arranging, cleaning, ordering and familiarizing oneself with the data. In addition to the basic statistical summaries and data plots, we strongly recommend to perform partial correlation analysis that in a multi-variable context can bring out causal and other groupings of variables.

- Both regression and classification should be performed, in tandem–one feeding the other. The unsupervised classification method, \(k\)-means, can provide initial clustering, that is then useful for the SVM, supervised classification. Both then provide important input for the choice of explanatory variables (paramters, features) in the regression steps. A single algorithm will very rarely be able to capture reliably all the underlying physical phenomena. That is why it is always advisable to try several, and then retain the ones that are best for each predicted response variable.

- Together, the computed machine learning models will provide the sought-for surrogate models.

In our case, we were able to robustly predict which combinations, and groups of design variables would give optimnal battery manufacturing performances.

An important caveat is: do not rely blindly on the performance metrics output by the ML methods. These can often be misleading and must be carefully chosen to measure what you want to achieve. It is not because you have a good accuracy, that you have a good model… Please see this post for a more detailed explanation of this often overlooked point.